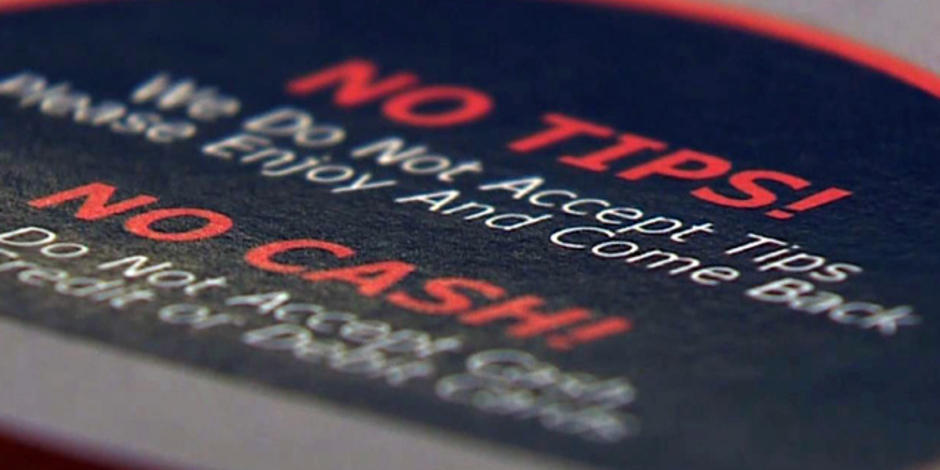

No-tip Restaurants Gaining Few Fans

There aren’t many issues on which edgy Momofuku chef/owner David Chang and a Koch brothers-funded conservative think tank would see eye-to-eye. But the no-tipping movement is one of them. Both voice concern that changes to waitstaff compensation schemes triggered by $15 an hour minimum wage mandates could have a detrimental effect on restaurant economics, particularly at mid-sized operations.

The outspoken Chang made his remarks in an hour-long podcast downloadable here: The content is also summarized on Eater.

Chang has nearly 1,000 employees on the payroll across his Momofuku empire. He has banned tipping at just one of his restaurants, the new Nishi in Manhattan, setting menu prices high and paying hourly rates that translate to a living wage for both the front and back of the house.

He’s of two minds about the value of no-tip schemes and $15 an hour minimum wage mandates.

“Socially and politically I’m pretty damn liberal,” he says. “Socially—I wouldn’t say I’m a socialist but I’m behind everything we’re doing, what the government’s doing (raising the minimum wage) I would also want. But as a business owner, it doesn’t make any f***ing sense….It’s painting us in a corner and there’s no room to grow.

“The $15 minimum wage in New York, 100 percent behind that. But…I don’t know how they’re making this calculation. I’m afraid of what’s going to happen. A good fine dining restaurant could do like two to five percent margins, fast food 10 to 20 percent. So, anything over 10 percent is a good year…the wages are going to really cut into the margins.”

Many restaurants could wind up struggling.

“My fear is the medium-sized restaurant, from 50 to 75 seats. It’s just too hard to run, we might see the extinction of it. That could be a result of labor. You need a certain number of people to run a restaurant. I don’t know if the numbers are going to work.

His prediction: “The next two years are going to be very, very telling of the future of the culinary industry,” he says. “The no-tipping is great, but I’m still reserving my judgment until I see it work. Right now I think it works for a certain kind of restaurant. I don’t know if it works for all restaurants.”

Dallas-based National Center for Policy Analysis (NCPA), supported in part by the Koch brothers, shares Chang’s skepticism. Its recent report, “Should Tipping Be Abolished?,” examines the forces at play in the no-tip movement and sees trouble ahead for many restaurant businesses.

“The arguments for replacing tipping with a higher minimum wage fail on both factual and theoretical grounds, at least for casual, sit-down restaurants, which have been identified as a target of laws that abolish tipping,” writes author and senior NCPA fellow Richard McKenzie.

The report acknowledges the need for a more equitable compensation scheme in restaurants. But it concludes that mandates aren’t the way to get one.

“Overall, the various arguments labor advocates make for abolishing tipping are probably well-intended, with the welfare of servers at heart,” McKenzie points out. “The arguments certainly sound good, but they are divorced from the key economic realities of the server-labor and restaurant market economics they have highlighted. While some restaurants might find that a ‘hospitality included’ pricing plan works best for them, it will not necessarily work for others.

What would that not working look like?

“The evidence indicates that eliminating tipping will lower servers’ incentives to provide quality service, which suggests that not only will customers’ experiences suffer, restaurants’ costs of monitoring servers will increase, potentially undercutting the incomes of both servers and owners.”

The NCPA report primarily revisits material that has already come to light elsewhere. However, the think tank did some original research of its own, and the data is enlightening.

“An informal survey of 40 servers in moderately priced sit-down restaurants (on par with Applebee’s) was conducted in California’s Orange County. The servers were asked what hourly wage rate would they need to voluntarily forgo their current minimum wage and all tips. The hourly pay rate given ranged from $18 to $50, with a median hourly rate of $30. All the servers were quick to assert that if tipping were replaced by a fixed hourly rate of pay, service would suffer significantly, at least on average.”

Service could deteriorate in a number of ways. Among them: Servers in a no-tip situation may not tolerate fussy or otherwise problematic customers as they once might have. Vigorous upselling of check-building extras could come to a halt. And why push to turn tables during busy times when all it means is more work for the server for the same money? The net effect could be that the server’s job could get easier, but the restaurant manager’s job could get a lot tougher.

Server turnover rates could climb, too. The report cites the experience of San Francisco restaurants Bar Agricole and Trou Normand, which eliminated tipping in 2015, only to reverse course 10 months later. During the no-tip experiment, menu prices rose 20 percent, with the proceeds used to increase the hourly wages for cooks and servers.

“Servers experienced an hourly wage drop from a range of $35-$45 to $20-$35,” the report notes. “Seventy percent of servers quit while the no-tip policy was in place.”

Thad Ogler, who owns these two restaurants, told media outlets that “we were spending a lot of time and energy hiring and training, and rehiring and training. We were hoping more restaurants would switch [to no tip] but, for now, it’s been impossible to compete with more traditional places in keeping front of the house staff who prefer the control and upside of the tip system.”

The sample size is small so far, but it appears that not all servers favor a no-tip policy. Keep this in mind while pondering whether such a system would solve problems or just create new ones for your restaurant.