Apr 28, 2018

Ashok Selvam | Eater Chicago | April 27, 2018

The promising seafood pop-up restaurant from the opening chef at the acclaimed and short lived Honey’s has found a permanent home in Logan Square. Good Fortune will move into the space vacated by The General at 2528 N. California Avenue. Executive chef Charles Welch and creative director Andrew Miller launched the pop-up in August and it lasted through October while whetting the public’s appetitive and earning critical praise.

A news release and spokesperson didn’t provide an opening date. However, diners can already book reservations via Reserve. The first-available date is July 19. Whether they’re calling that the official opening date remains to be seen.

The restaurant is a 44-seater with a nine-seat bar and a 14-seat patio. The pop-up featured a casual atmosphere mixed in with food that showcased Welch’s fine dining skills. Creative spins on scallops, which were reminiscent of taco al pastor, and a braised octopus stood out, according to critic Michael Nagrant. The permanant spot will have more Mediterranean offerings.

CONTINUE READING

Apr 20, 2018

Jonathan Maze | Restaurant Business | April 19, 2018

As the labor market continues to tighten, restaurants are encountering a new competitor for a thinning pool of employees: Uber.

The ride-hailing service and similar companies that make up the gig economy are adding a new layer to the challenges of finding good workers.

Already facing high turnover and decreasing teenage labor participation, restaurants now have to compete with the independence and flexibility that such services provide to drivers.

“Restaurants are very vulnerable to the gig economy,” Victor Fernandez, executive director of insights and knowledge for the data firm TDn2K, said during the Restaurant Leadership Conference in Phoenix this week. When analyzing people who drive for companies such as Uber and Lyft, he said, “We’re really the primary match for that employee.”

Fernandez noted that two out of three front-of-house employees are part-time, working 25 hours. And they typically make low wages.

Those workers can be tempted by the flexible hours and independence that working for one of the delivery or ride-hailing services provides.

“Someone who suddenly discovers Uber is not looking at replacing 40 hours, they’re replacing 25,” Fernandez said. “We’re not offering full-time jobs. That’s why it’s so easy from the money perspective, the money and the flexibility.”

Low unemployment and strong hiring by restaurants have created an environment in which it’s difficult to find employees. Restaurants have added 200,000 jobs over the past year, according to federal data, and have added jobs at a higher-than-average rate for years.

That has shed a light on the competition the industry is facing for a dwindling pool of available workers from a growing number of competitors. Restaurants simply aren’t used to competing with companies that can offer the flexibility that ride-hailing services and other gig employers can provide.

CONTINUE READING

Apr 14, 2018

Ashok Selvam | Eater Chicago | April 12, 2018

Roscoe Village is getting a restaurant featuring cuisine from southern France. Slated to open this summer, Le Sud is a new restaurant featuring food from chef Andy Motto, last seen in suburban Evanston at Quince, a restaurant that closed in 2015. The new spot, which has had an active social media presence via Facebook and Instagram for the last few months, will also feature rooftop dining at 2301 W. Roscoe Street.

Sandy Chen owns the restaurant, and she’s a familiar name for Chicagoans. Since 1994, she’s run Chen’s (formerly House of Dong Yuang), a Chinese restaurant in Lakeview. Chen has also run Koi Fine Asian Dining in Evanston. French food is an abrupt change for Chen, who also worked at Tang Dynasty, a long-shuttered Chinese restaurant off the Mag Mile. But she’s ready to break out and try something different.

“It’s my dream come true,” Chen said.

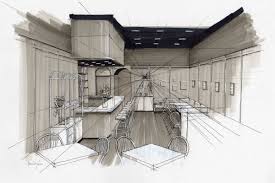

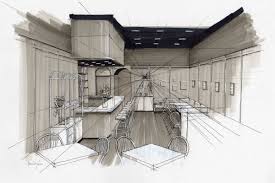

Chen said a visit to Nice, France inspired her and that the city reminded her of where she grew up in southern China. They’ll focus on food from Provence, a southeastern region of France near the Mediterranean Sea. The space will have room for about 120 seats inside over two floors and they’ll have bars on each level. Chen’s particularly excited about a rooftop space that has room for about 60. The restaurant was a Mexican spot, Que Rico, before Chen took over. Eventually, they’ll also have a sidewalk patio.

CONTINUE READING

Apr 6, 2018

Leslie Wu | Forbes | March 31, 2018

Opening night at a restaurant can be fraught with peril — thanks to Yelp and social media, backlash over perceived flaws are immediately shared within hours of opening, and a restaurant staff has less time than before to get their bearings.

Kevin Boehm and Rob Katz, cofounders of Chicago’s Boka Restaurant Group plan out each opening with precision, trying to anticipate potential minefields — a luxury of larger budgets compared to their first starts. “I think in the old days, when you were running out of cash, and you were like ‘We’ve got to open up now!’, that was when you saw the problems. We open when we’re ready now, and we add that in as part of the budget,” says Boehm.

This planning stage translates to significantly more time in the space for all the staff to get acclimatized. “In the old days, we had to get inspected, pass inspection, and then open in two days,” recalls Boehm. “Now, once we pass inspection, we like to have a certain number of days in the space before we actually open up a restaurant: 30 days of front of house training, 17 days with the chefs inside of the finished space cooking, two days of staff on staff, and three or four practice dinners before we even open up the doors. At this point, we don’t like unknowns.”

It hasn’t always been this easy, however — over the years, Boehm and Katz have learned a lot about the trials and tribulations about the owner/operator life. For those who may be considering opening a restaurant, here are five tips from the trenches as to planning the big day and beyond.

1. Build the foundations as soon as possible.

At the beginning of their partnership, Boehm and Katz tried to take care of all the minutia by themselves, instead of letting others pitch in. “We truly ran ourselves into the ground, to the point where we were close to nervous breakdowns. And what we needed to do, as we expanded — and we should have done it faster — was build our infrastructure,” says Katz. “Instead, we basically hoarded our information and did not delegate properly because we just didn’t have faith and trust in anyone else. When we finally did, it turned out to be the greatest thing that ever happened to us.” [For more tips on delegation, read How Two Workaholic Entrepreneurs Learned Work Life Balance And Delegation].

2. Sweat the small stuff.

Fussing with the chair selection and table placement for the first day comes naturally to a new restaurateur, but to keep up that eagle eye as the weeks or years go on can be a challenge. For Boehm and Katz, however, being vigilant is key. “It’s just one thing, paying attention to the details in the restaurant business is absolutely imperative, because the margins are so small, there’s so very little room for error,” says Katz.

CONTINUE READING

Mar 30, 2018

Elliot Richardson | Crain’s Chicago Business | March 15, 2018

New restaurants spur economic development and create jobs in communities across the state. They bring people into neighborhood business districts and expose patrons to nearby retailers and small businesses. Unfortunately, entrepreneurs attempting to open an establishment in Illinois face an archaic law that prohibits them from serving alcohol within 100 feet of a religious institution, school, hospital or military station.

This law stymies the growth of local economies, often in areas where new opportunities are needed most. And it paints all communities with a single brush instead of allowing local leaders to determine the restrictions that best serve their businesses and residents.

The Liquor Control Act of 1934 became law in Illinois shortly after the 18th Amendment was repealed. It prohibits the sale of alcohol within 100 feet of the institutions identified above but provides restaurants the opportunity to procure a specific exemption for their establishments. However, obtaining an exemption takes an actual act of the Illinois General Assembly.

Specifically, for a single business to receive an exemption, a bill must be drafted, passed by the Legislature and signed into law by the governor. Most small-business owners simply don’t have the time or resources to tackle this burdensome process.

In the 84 years since this became the law of the land, only 75 businesses have been granted such an exemption.

CONTINUE READING

Mar 22, 2018

Jillian Kramer | Food & Wine | March 15, 2018

“Match the restaurant to the location.”

We’ve all seen it happen: one day, there’s a brand-new restaurant around the corner that we can’t wait to try and the next day, that same restaurant is closed—for good.

Statistics paint a grim picture for anyone who dreams of opening a restaurant. In New York, for example, 80 percent of restaurants fail within five years. And regardless of their location, about 60 percent of restaurants close in the first year, one study shows.

Luckily, from those failures come lessons—and two restaurateurs, who now own successful spots, are here to share what they learned from their own shutterings.

“Match the restaurant to the location.”

When James Groetzinger, who owns Warehouse and Calhoun Street Tavern, opened Parlor Deluxe in 2015, “it was a little bit ahead of its time for the location,” he says. “The location was on a one-way street with no nearby parking lots, making it street parking only. It was also before a lot of construction was moving farther up town, so we weren’t getting a ton of foot traffic passing by.”

But since the restaurant closed in 2016, “the street has become a two-way,” Groetzinger says, “and they’ve built a huge parking deck a couple blocks over.” Had Groetzinger waited another year to launch the restaurant, he might have had better luck, a lesson in choosing the right location.

“Eliminate dress codes.”

Carl Sobocinski, owner of Table 301 Restaurant Group, believes today’s diner wants to dress casually—but two of his former restaurants, Restaurant O and Devereaux’s, had dress codes. “I never thought they were that strict but the patrons who were turned away did, and they were sure to tell their friends that we had a dress code,” he says. (The restaurants’ dress code included no shorts, no flip-flops and no baseball caps.)

“The [no shorts rule] was the biggest issue with patrons because we are in South Carolina where summer nights are humid and can reach temperatures in the 90s, even during dinner hours,” he says. Lesson learned: “We dropped the dress code after a few months, but the damage was already done.”

CONTINUE READING